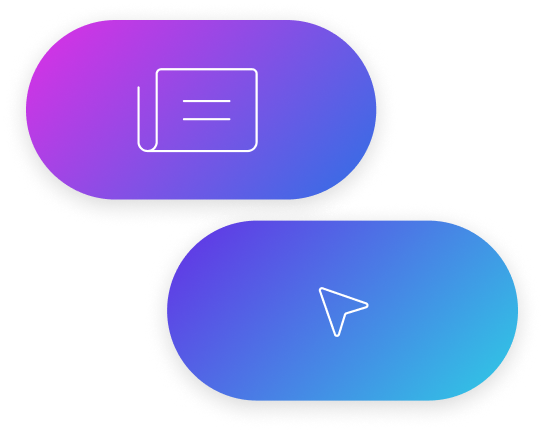

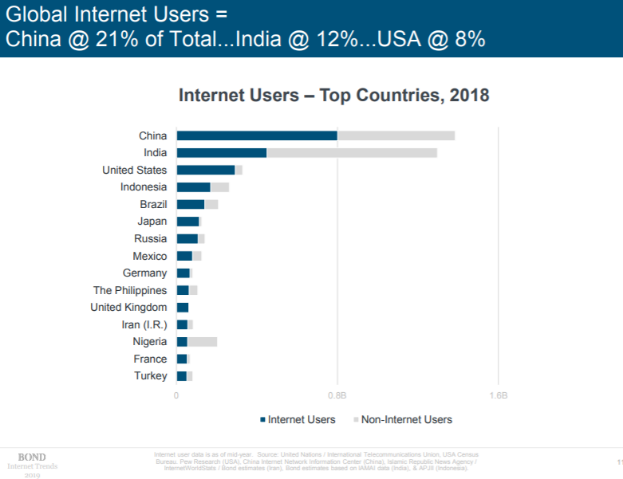

Nearly 50% of the world’s population still has no access to the internet, a phenomenon known as the digital divide. The digital divide is the gap between those people who have access to Information and Communication Technologies (ICT), primarily the Internet, and those who have limited or no access.

In today’s day and age, with all our global communications capabilities, how can it be possible that half of the world’s population has no access to basic internet!? Particularly given that we now know, without doubt, that there is a clear correlation between access to ICT services and prosperity growth. The GSMA cite several reports that show the impact of mobile adoption. A 10 percentage point increase in mobile penetration increases total factor productivity over the long run by 4.2 percentage points. A 10% substitution from 2G to 3G penetration increases GDP per capita growth by, on average, 0.15 points. In turn, the availability of Internet services can represent up to 25% of overall GDP growth [1]. The benefits of good, easily accessible ICT services are 100% clear.

Telecommunications is an extremely complex business but if we step right back, how can we have close to 100% penetration in some markets but less than 50% internet penetration in others?

To have such stark disparities, I can only believe that the current telecoms model is broken when considering the communication demands of the world we live in today.

There are many reasons put forward for the causes of the digital divide, but we can broadly categorise these as; a lack of motivation to access and a lack of material access.

Motivational access

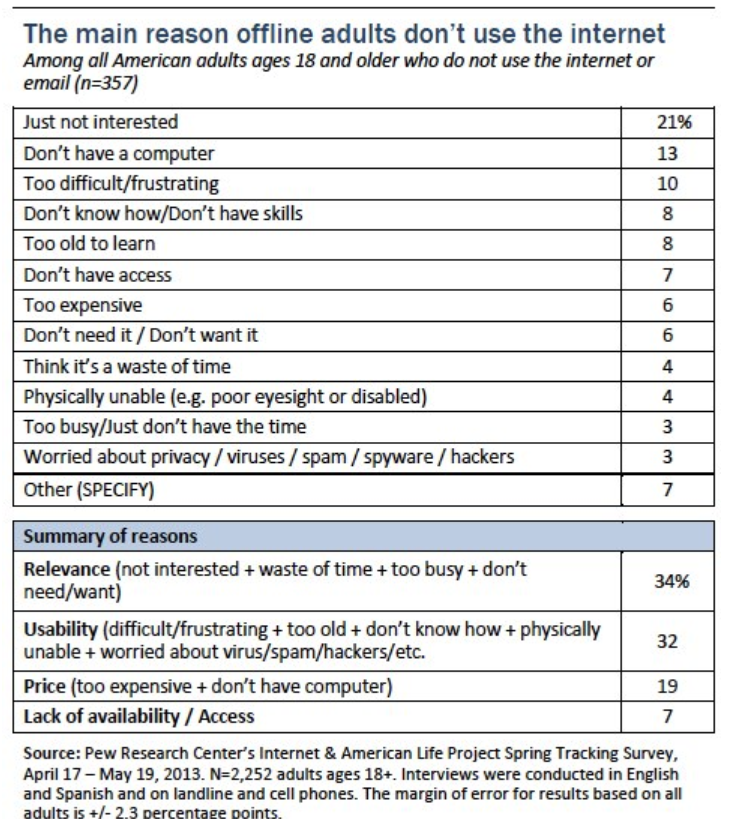

Motivational access is the desire to gain access to ICT services and to connect to the Internet. The factors explaining the motivational access divide can be social, cultural, mental and psychological; for example, low levels of education and/or income, computer anxiety and lack of time. The most difficult area in which to make a shift in the digital divide is not the ‘have not’ but the ‘would not’. Those who have access to the internet but either don’t have the motivation to gain access or don’t have the computer literacy to do so. The latest findings from Pew Research [2] show that 10% of Americans do not use the internet, with one of the major reasons being that they have no interest in doing so.

A 2013 survey conducted by Pew showed that 15% of Americans did not go online and 34% of that 15%, when surveyed, said that they did not believe it was relevant to them.

Internet penetration in the US is continually improving but the issue is not just one of material access but also one of desire to access. Once affordable access and computing devices are available to all, the next step is to teach new users how to put the technology to work for them. The solutions of increasing access and education must go hand in hand.

Material Access

Material access becomes a consideration for a user when motivational access to ICT exists. Material access is also known as accessibility and is influenced primarily by income and therefore affordability of ICT services.

Global examples of this start from an extreme, such as in Somalia where internet usage is 9.5% of the population in 2019 (Internet World Stats, 2019). Due to cost and the shortage of ICT infrastructure, there is little online learning in Somalia, for example. Having experienced a long history of civil unrest, the country has suffered from a lack of investment in ICT infrastructure. Understandably the majority of funding or disposable income tends to go towards basic needs like food, healthcare and shelter.

In the Americas, statistics suggest that the further south you go, the greater the divide. In Canada, only 7% of the population are not internet users (Internet World Stats, 2019). In the USA, 10% of the population does not use the internet (Internet Users, 2019). Data collected by the Pew Research Centre (Rainie, 2013) shows that household income has a direct link to the quality of internet access. An example of this is, that out of those who earn under $10,000 a year 70% have access to the internet, compared with those who earn over $100,000 where 90% have access. The issue of access appears to widen as we move further south with 66% of Mexicans, 67% of Bolivians and 67% of Peruvians not having access to the internet (Internet Users, 2019).

There have been many government initiatives to bridge the digital divide such as the Lifeline program in the USA, which is a Federal program that provides subsidised phone and Internet services for those who qualify. Although successful in many ways, we should question the sustainability of local or federal government-led subsidy programs as a means to creating a long-term solution for the global issue of the Digital Divide. The Lifeline program, as an example, addresses affordability issues by making ICT services more attainable for lower income brackets but primarily where the ICT infrastructure already exists. However, that does not address the larger issue of accessibility in rural or remote areas where ICT infrastructure doesn’t exist, and where it is not viable for operators to build out infrastructure.

Other such initiatives include national broadband programs, such as Australia’s NBN. These programs are using government funds to build out fundamental infrastructure such as high-speed, nationwide broadband networks, often based on the deployment of fibre optic networks right to the customer’s premises, known as Fibre To The Home (FttH). These initiatives, although bringing many benefits, have had their challenges in terms of return on investment and the effectiveness of making broadband more accessible and or affordable to end users [3]. Australia’s NBN network has had its fair share of criticism and recent reports suggest that the cost of the network will double from initial budget estimates to circa $50bn. A change in government brought about a revision of the NBN strategy, and in order to limit cost exposure, a mix of lower-cost technologies has been proposed to complete the network. However, some of the original founders of the program have argued that the proposed technologies will reduce speeds and capacity to a level that negates the entire premise of the program. Many industry analysts will argue that government involvement in such programs is a fundamentally flawed strategy for reasons such as government culture or stakeholder priorities being the opposite of those required to run a profitable telecommunications network.

Operator economics challenges

If we were to look at the key challenges operators face when implementing a mobile network and overlay these against the challenges of bridging the digital divide, we can see several friction points arise. Very broadly speaking, we could say that the main challenges a new mobile network faces revolve around costs of setup, operation and regulatory factors. The main driver of success is achieving economies of scale, that is, being able to attract enough customers onto the network to bring the average cost per user lower than average revenue per user. Often in the early years of an operator’s lifecycle, they will run at a loss until the customer base grows and economies of scale are achieved.

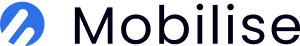

Discussing the cost challenge, the lack of coverage in rural areas is the by-product of a basic economic challenge: deploying infrastructure in remote areas, such as fibre backhaul or base stations, can be twice as expensive as in urban areas, while revenue opportunities can be a fraction of that in urban areas. A combination that makes the business case to deploy infrastructure in these areas completely unviable using today’s telecoms business model. The table below from GSMA’s 2016 “Unlocking Rural Coverage Enablers for Commercially Sustainable Mobile Network Expansion” report highlights the challenges well. We can see that if urban locations represent the perfect economic scenario for an operator, rural and remote areas become significantly more challenging to achieve ROI.

(Source: GSMA Report, “Unlocking Rural Coverage enablers for commercially sustainable mobile network expansion”)

With 60% of the world’s population still living in rural areas and about 20% in remote areas, extending mobile broadband coverage to reach these populations is very difficult with today’s technologies or cost models. Firstly, because the populations tend to be spread out across wide areas, it makes the business model for building a site in such areas highly unprofitable. Rural areas represent over 90% of the land surface on earth with population density often below 100 people per square kilometre. The GSMA estimates that to be profitable, a site needs around 3000 active users daily. This means that only rural areas, where the population concentration is equivalent to this within a 25 km2 area (the coverage range of a single site using 900MHz spectrum), can be covered on a commercially sustainable basis.

Negative impacts of regulation

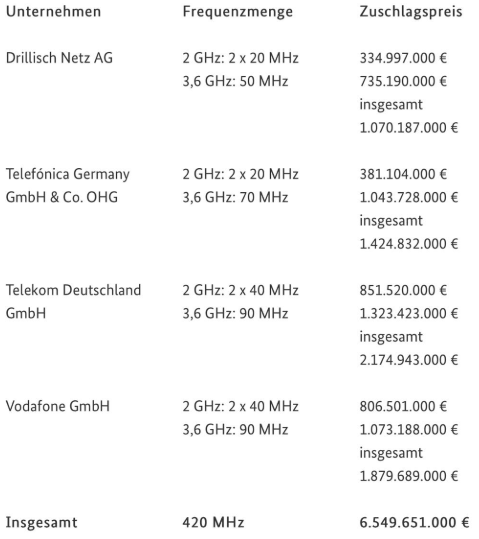

Looking at the regulatory environment, today, in our opinion, we can see significant issues with the existing framework which, among other things, is slow-moving and has extremely high barriers to entry. Many of the regulatory policies that have evolved over the years have been born from genuine market concerns, i.e. driving competition, protecting consumers, driving accessibility etc. However, there are clear examples of how today’s commonly used regulatory framework is negatively impacting the growth and innovation of telecommunications services. An example is mobile spectrum auctions. Governments raise large sums by auctioning off spectrum to the highest bidder. The recent German 5G spectrum auctions could be an example, where the German government raised a colossal €6.5 Billion from 4 operators. Many local analysts report that this will drive value out of the market because operators will need to keep prices high in order to recoup their investment or have sufficient capital going forward to invest in network expansion [4].

It is arguable that in some ways, these spectrum costs hinder innovation because operators are forced into the mindset of low-risk strategies that offer the safest, or most probable, route to receiving a return on their huge investments. This is as opposed to operators pushing forward with more innovative strategies, that, yes, could be deemed riskier by traditional measures but would likely spur greater levels of innovation for the future.

Regulators

Could regulators do more to encourage the principle of open access spectrum? Such as initiatives similar to CBRS in the US, freeing operators of the cost burden of the spectrum could mean they could have additional funds to use towards investment in network or innovation. Perhaps that would be a more positive regulatory mindset; remove spectrum costs but mandate operators to spend x amount per year on R&D. Surely this would spur new products and services innovation and eventually lead to net incremental revenues, providing higher taxable revenues. Could these taxes substitute, or even surpass, the sums gained by governments through spectrum auctions?

So, what is the answer you say? There is certainly no easy answer but what is clear is that today’s telecommunications model is not fit for purpose if the objective is to connect those most affected by the digital divide in rural or remote areas. When considering the infrastructure cost constraints mentioned above, there clearly needs to be innovation in radio, core and backhaul technologies to overcome the digital divide in a sustainable, long-term way. Perhaps the introduction of a more flexible Core network and RAN technologies, reducing cell site infrastructure costs could be a solution. However, you then have the issue of backhaul and as of today, there are no technologies readily available to dramatically reduce these costs. So easier said than done.

There are interesting movements in the area of Low Earth Orbit (LEO) satellite communications networks with the likes of Amazon, SpaceX and OneWeb all moving into the industry with aspirations to fill the digital divide. The difference with LEO networks, compared to traditional GEO stationary satellite networks, is that their orbit around the earth is at a lower altitude and this, in short, has the potential to offer comparable bandwidth and latency to that of existing wireline broadband technologies like fibre optic or coaxial. Perhaps this could be an option for backhaul. SpaceX, with its Starlink project, has been one of the more vocal organisations about its satellite network plans. And even though they intend to launch some 12,000 satellites at a reported $10bn investment, estimates suggest this will still only support less than 10% of the world’s bandwidth requirements (reports on this number vary, so should be taken with a grain of salt). Therefore, their impact may be limited. Starlink does seem to suggest they will offer services directly to the consumer market, so it will be interesting to see how the regulation plays out under this model. They will effectively have a global communications network that spans multiple geographies and multiple countries, each with its own underlying regulatory frameworks. So how will Starlink cater for these differing local requirements and at the same time build a scalable global operating model? Then there is still the question of whether these networks can reach the economies of scale required to significantly reduce costs versus existing technologies. You also have the issue of electricity supply to connect base stations in rural or remote areas, which could be addressed using solar power technology. However, then you need to consider the solar panel and installation costs.

So there appears to be no easy answer yet, but if there was one, I guess someone would have done it by now!

To be continued….!

[2] – https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/04/22/some-americans-dont-use-the-internet-who-are-they/

[4] – https://www.ft.com/content/c6a6a47c-8d44-11e9-a1c1-51bf8f989972